Observant readers might recognize this title, and remember that there was once a report of a journey to the Getty Center in the City of Angels that promised a sequel (a “part one” does beg a “part two”, after all). Well, here it is! Apologies for the great delay. I’ve never really developed a strong writing ethic, I’m afraid, so this essay languished in my notes for many moons.

NOTE: All photographs were taken by © Jay Logan , and all captions for museum exhibit pieces were adapted from text from the exhibit itself, which were photographed during the visit.

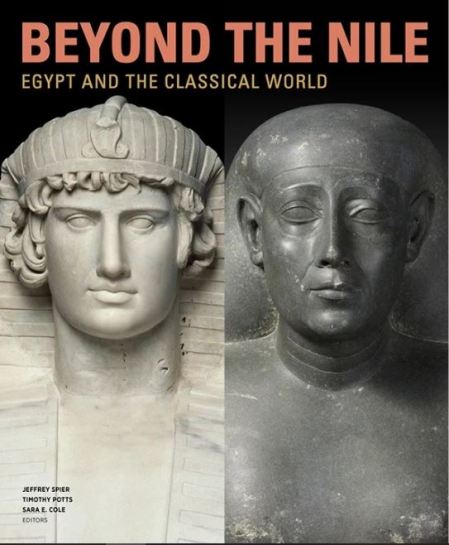

My journey in the Getty Center’s exhibit “Beyond the Nile: Egypt and the Classical World” began and ended with Antinous, as one might expect since he was the raison d’etre for my trip, but I actually do mean this literally. His face was the first thing I saw upon entering, for it was his face on the cover of the exhibition book, which was prominently displayed in the gift shoppe at the entrance to the exhibit (which, let me tell ya, is not fair and very distracting! So many pretties….). And his bust was front and center in the last exhibit; journey’s end, the heart of the labyrinth. But what of the journey?

One of the things the exhibit did beautifully was capture the context from which Antinous grew. He was not the first mortal to be worshipped as a god, by any means. Outside the realm of myth, Alexander the Great beat him to that by several centuries. There was also the Ptolemies, the dynasty that took over rule of Egypt after Alexander, who apparently all received divine honors upon their own deaths. And while the Hellenistic period is depicted as being highly syncretic and cosmopolitan (and it was), it was just the latest in a long line of cultural exchange and mixing that occurred between Egypt and the rest of the world. The exhibit took a serpentine route from Egypt’s beginnings through to its diverse interactions with the Mediterranean world.

At the time, I had been reading Laura Tempest Zakroff‘s latest book on Sigil Witchery, which takes an artist’s approach to seeing and crafting sigils. As a result I found my eye being drawn to the variety of motifs and symbols on the ancient artwork, often getting quite close to the artifacts in question to get a good look, seeing how they were represented and depicted. I also found myself drawn to the grave stele and statues of various priests. I felt…a kinship to them, in a way that I’ve never really thought of before, often feeling moved to address them as Brother and Sister. This was probably due in large part to my recent elevation to the third degree in my Wiccan tradition, which among other things denotes being a Tradition Keeper, and which coincided with my own personal acknowledgement and acceptance of the role as a Priest of Antinous; not something I say lightly. That’s what I am, though, and that’s what I do – the priestly work of the Beautiful Boy. It was inspiring, and a delight, to see so many faces (and torsos!) of fellow Greco-Egyptian priests and priestesses.

Noticeable in his absence were any images depicting Emperor Hadrian. The last exhibit held many items from his Villa in Tivoli, including the aforementioned bust of Antinous, but not a single representation of him, not even a coin.[1] It was as if he lived on through his work, or perhaps through his beloved Antinous.

EGYPTIANIZING SCULPTURE FROM HADRIAN’S VILLA

During the Roman emperor Hadrian’s visit to Egypt in AD 130-131, his companion Antinous tragically drowned in the Nile River. The grieving ruler memorialized his young lover by founding the city of Antinoopolis near the site of his death. He also established a Roman cult in which Antinous was honored as a semidivine hero and equated with Osiris, the Egyptian god of the underworld.

Hadrian’s lavish imperial villa at Tivoli, northeast of Rome, was decorated with numerous statues of Antinous in Egyptian costume, as well as many other sculptures with Egyptian imagery. The enormous complex was designed to evoke the ruler’s wide-ranging travels throughout the Roman Empire. A terraced garden with a long pool was named Canopus after the site near Alexandria in Egypt, and a sanctuary that may have been dedicated to Antinous contained an obelisk in his memory.

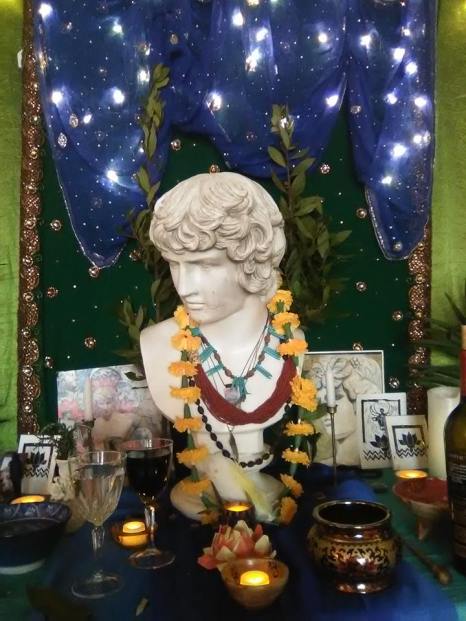

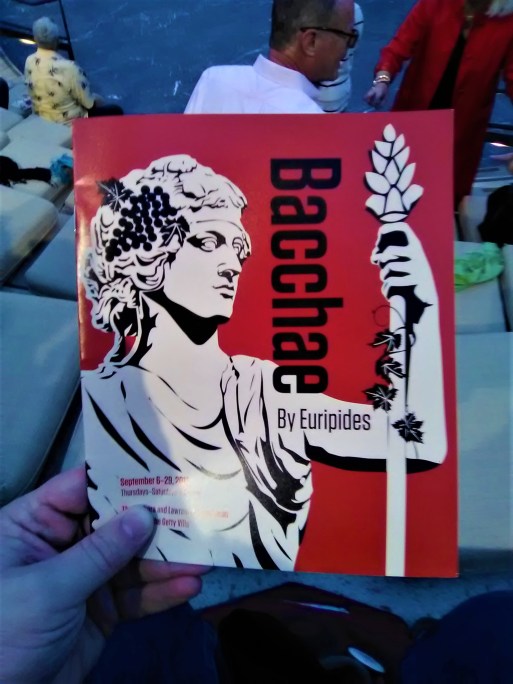

What was odd, and which came as a great surprise to me, was that I didn’t feel any closer to Antinous for being in his physical presence. Here was a statue from the ancient world, that I had seen before only in pictures, which was made in the years immediately following his death, and which resided in Hadrian’s own Villa in Tivoli, an object of veneration and worship, but I felt no closer to my god. In fact, I felt more “religious juice,” as it were, the night before, while watching The Bacchae on stage at the Getty Villa. The Bacchic Chorus was amazing, as I have mentioned, and I had to constrain myself from diving into the fray and joining their merry band (To the Mountain! To the Mountain!).

Perhaps that’s where the difference lies. For all that the word “museum” would seem to denote being a “temple to the Muses,” the fact remains is that it’s not a temple. While this one in particular contained objects that I would deem to be sacred, the only sacrifice being performed was at the register, and that not for the benefit of the gods. And there’s an immediacy, an aliveness to drama (especially one devoted to Dionysos!), which is not the same as stationary statues that aren’t receiving fragrant incense; that aren’t being sung to, being prayed to. Maybe if it hadn’t been as busy as it was, I could’ve gotten some singing in…. 😉

At the same time, though, I left the museum content, my cup filled. There was beautiful art to be seen and connection to priests and priestesses before, as well as a new realization. For perhaps there was another difference between the play and the museum, in that I was already close to Antinous. I’ve had devotion to him for many years now, been initiated into his Mysteries. After all, how can I be any closer to him than that, and when I encounter him everyday at my own altar? I was reminded of this poignant moment from Doreen Valiente’s “Charge of the Goddess”:

If that which you seek

You find not within you

You will never find it without you

For behold, I have been with you from the beginning,

And I am that which is attained

At the end of desire.

The Gods can be far away, but they come at the speed of thought, at the speed of prayer.

And who knows? Perhaps I’ll feel differently after I’ve made pilgrimage to some of his sacred sites; walked the land that he once walked, touch the waters he drowned in with my own fingers. The Land has its own ways of Knowing, and Antinous in those Places will likely be quite different than as I’ve experienced him so far. One can hope….

The final face in the exhibit. Head of Caracalla. Romano-Egyptian, 211-217 CE; found in Coptos, Egypt. The Roman emperor Caracalla (ruled 198-217) is shown wearing a uraeus (royal cobra) to mark his status as pharaoh. This head, carved from a hard Egyptian stone, once belonged to a colossal figure that stood in the Temple of Isis in Coptos, Egypt. It carefully copies the close-cropped hair, furrowed brow, and distinctive scowling expression of the ruler’s official portrait, which was first displayed in Rome in 211 CE and is known from many versions in marble.

[1] Apparently in this I was mistaken. Looking through the exhibition catalog for “Beyond the Nile: Egypt and the Classical World” I was able to find a single coin of Hadrian (cat. 182). Somehow, I must’ve missed it….